Blog

—————————

The politics of LGBTQIA+ mental health:

Towards a depathologising and intersectional practice

by Tomás Ojeda

Those of us who work in the field of mental health and practice as psychotherapists, researchers, counsellors and community workers have heard iterations of the same statement multiple times: LGBTQIA+ people experience high rates of anxiety, depression and distress compared to the heterosexual and cisgender population, which can be explained by the social effects of discrimination, unemployment and school violence, hetero-cissexism and LGBTQIA+-phobia, among others.

Decades of research and activism (Barrientos, 2019; Goetz & Keuroghlian, 2024), as well as more than fifty years of consensus across diverse scientific communities around the world, confirm time and again the validity of this assertion and its sad currency today: despite progress in LGBTQIA+ rights in many parts of the world, health disparities, institutional violence and barriers to accessing affirmative and depathologising care continue to play a central role in the narratives we tell about the wellbeing of minoritised communities (Boden-Stuart, McGlynn, Smith, Jones, & Hirani, 2022; Tomicic, Martínez & del Pino, 2019; Zeeman et al. 2018). While mental ill-health affects both cis-heterosexual populations and sex-gender dissident communities – as capitalism and neoliberal health policies do not discriminate in this regard– the reasons behind LGBTQIA+ health inequalities need to be addressed specifically and from an intersectional perspective (Reyes, Mayorga & de Araújo Menezes, 2017).

We know, for example, that poor health outcomes are unequally distributed among people across class, migration status, gender, age, disability, educational level and territorial belonging (Galaz Valderrama, Cea, Molina, Castro, & Ortega, 2022). This uneven distribution challenges us to look at the problem not as the result of a sum of categories of difference but in their interaction. In other words, whether a person is bisexual, trans, intersex, gay, lesbian or non-binary is not enough in itself to explain health inequalities, as sexuality and gender are not the only categories that matter.

Taking up the challenge to explain the drivers of poor health, we came together as a group of mental health professionals and activists who work with LGBTQIA+ people in Chile and the UK, to discuss these issues and exchange knowledge about our practice during March and May 2023. We shared our fears at the hostility towards trans health and its impact on people’s wellbeing, as well as the joys and challenges involved in working towards a better mental health for all. We wanted to write about the encounters we had through a research report, and in this blog piece I will share some of the main findings of these exchanges and possible responses to the problem of health disparities, focusing specifically on the principles that orient our work and the place of ‘politics’ in mental health practice.

The research project:

LGBTQIA+ mental health knowledge exchange

What are the main challenges that mental health professionals face when working with LGBTQIA+ people? What does working from a depathologising and affirmative approach mean for us? What socio-political, cultural, economic and institutional contexts must be considered when thinking about this work? How do we build solidarity networks to resist the attacks, moral panics, and gender anxieties articulated against affirmative care?

These and other questions inspired a series of three Knowledge Exchange Workshops that were part of my postdoctoral project “The Multiple Lives of Sexual and Gender Diversity in the Psy Disciplines”, which were supported by the Economic and Social Research Council and the South Coast Doctoral Training Partnership. The meetings were attended by a group of fifteen mental health professionals from the cities of Valparaíso, Concepción and Santiago (Chile), and Brighton and Hove (UK), and aimed at exchanging knowledge on LGBTQIA+ mental health and learning about the state of health policies in both countries.

Through knowledge exchange methods, we wanted to understand what a depathologising, reparative, affirmative and intersectional approach to LGBTQIA+ mental health means and does, looking specifically at the knowledge and practices that come from activist and academic spaces, as well as those that emerge from our experiences as psychotherapists, activists and researchers—most of whom are part of the same community we work with.

Depathologisation, reparation, affirmation, and intersectionality:

During our conversations, we realised that many of these approaches are taken for granted. For example, it is widespread to hear that if we work with LGBTQIA+ people, of course we work from a depathologising and intersectional perspective. And we often repeat this without much reflection; sometimes even as slogans to certify our progressive credentials or as mere descriptors of the work we do. In doing so, the problem is that we risk depoliticising the transformative potential of these concepts, as well as the history of depathologisation activism, and the struggles and resistances that have enabled us to work from affirmative and intersectional positions in the present. This is why we wanted to delve deeper into the ethical-political implications of these approaches, and to see how our own understandings of depathologisation and other related concepts changed as we talked and came across other definitions and experiences.

For us, mental health work that aims to be transformative of the oppressive structures which contribute to ill-health, must not only place depathologisation but also affirmation, intersectionality and reparation at the centre as the guiding axes of our praxis; hopefully altogether, not separately or in isolation, even if we still find it difficult to do so or we encounter resistance within the institutions where we work—for example, when we are told: yes to depathologising homosexuality but no to banning trans conversion ‘therapies’; yes to talking about intersectionality but no to revising our racial privilege and ableist biases.

The articulated work of these four principles must be on the horizon of our social-community practice. Not only as a declaration of principles but also as critical tools at the service of action and liberation. Here is a synthesis of our understanding of the four principles captured fully in our report:

- Depathologisation: a principle that recognises non-normative sexualities and genders as normal variants of our sexuality and gender, promoting an inclusive view of human diversity and respectful of people’s bodily autonomy. Depathologisation insists on challenging the gatekeeping power that psy and medical disciplines have historically had over non-heterosexual and trans experiences, questioning the disciplines’ diagnostic and certification claims on our identity.

- Reparation: puts into action concrete measures of redress and non-repetition of historical harms, abuses and human rights violations inflicted on minoritised groups through laws that criminalised our existences, abusive and non-consensual medical and psychological interventions (e.g. genital mutilation of intersex people, conversion practices), and through police and state violence (e.g. Chilean civil-military dictatorship).

- Affirmation: recognises, celebrates and values diverse gender identities and expressions, sexual and/or romantic orientations outside a pathologising framework. It acknowledges the right of people to explore their gender on their own terms and at their own time, leaving out expectations of an ideal outcome or destination. An affirmative approach recognises the risks associated with dis-affirming gender identity and expression, as well as the negative impact of messages that insist that gender must conform to the gender assigned at birth.

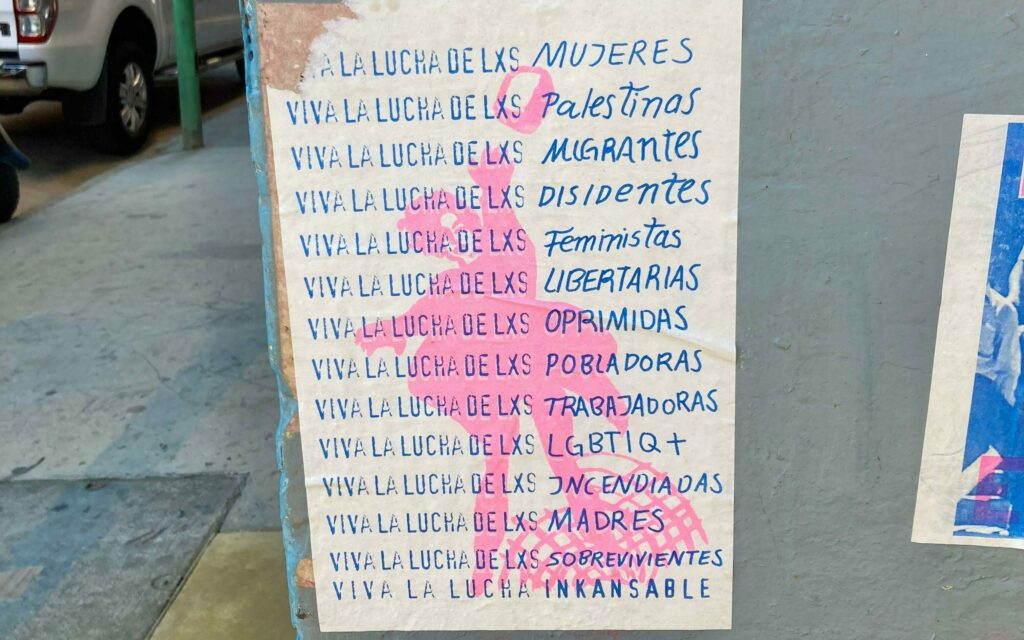

- Intersectionality: accounts for the ways in which different power structures (e.g. racial capitalism, ableism and cis-heteropatriarchy) intersect and shape people’s experiences of stress, oppression and access to health. An intersectional approach to mental health allows us to build alliances of solidarity and coalitions across struggles, and to challenge the myth that the rights of one group come at the expense of others. From here, we claim that promoting LGBTQIA+ mental health should not be understood as an identity agenda or as niche politics but rather as a common cause for social justice, care and the fight against all forms of violence and the atomisation of our struggles.

“The personal is political” – in the streets, institutions and our consulting rooms!

As well as discussing the principles that guide our practice, we also talked about the contexts in which we work and the socio-political and territorial conditions that shape people’s experiences of health and illness. By putting the onus on the social and political determinants that mark the life trajectories of those we accompany, some questions inevitably arise; although often uncomfortable, they are urgent and unavoidable:

- What does it mean to talk about LGBTQIA+ mental health in a context such as Chile, where denialism and relativisation of crimes against humanity that took place during the civil-military dictatorship marked the commemoration of its fiftieth anniversary in 2023; or where victims of eye trauma and police violence during the social uprising of 2019 have yet to see justice and receive reparations?

- What does it mean to work under a depathologising and affirmative approach in a context such as the United Kingdom where, until recently, the possibility of banning conversion practices was conditioned on the basis of sexual orientation and not on gender identity; or where a sixteen-year-old girl, Brianna Ghey, was stabbed to death and whose crime was driven, in part, by transphobia?

We know, because we have been told, that ‘politics’ is not very welcome in the institutions where we work; that when we speak back against racism or LGBTQIA+-phobic violence in our discipline, or when we cite the work of human rights groups we are labelled ‘activists’, as if it were a bad thing; as if our professional ‘neutrality’ was compromised. And the truth is that even if our experiences with activism and politics are different, our work has a clear and determined horizon in favour of social justice, trans-inclusive feminism, gender equality and scientific rigour, which we claim as political. And in this orientation we are ‘active’, not neutral: active in speaking out against the effects of trans-hatred violence, discrimination and dehumanisation of people. It is also about our lives and the commitments we have made to the communities we work with, which go beyond our consulting rooms and workplaces, sometimes even taking to the streets when we participate in pride marches and commemorate the international day against homo, bi and transphobia.

While the challenges of our work are many, one thing we learned through the workshops is that we cannot do all these things alone; that the conversations and encounters with different perspectives, in different locations and languages have transformative potential, and that working in alliances and coalitions with others is incredibly powerful. We invite you to read the report and share the material with your wider networks, so we can tackle the negative outcomes on the wellbeing of our communities together.

Santiago, Chile – 28 March, 2024

—————————————

Download Report

Ojeda, T., Boden-Stuart, Z., Bühring, V., Creedon, H., Jones, H., Méndez Contreras, J., … Salinas Mejías, P. (2023). LGBTQIA+ mental health in Chile and the UK: Depathologisation, affirmation and intersectionality in the experience of mental health professionals. Retrieved from https://affirminglgbtq.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/ReporteENG.pdf

References

Barrientos, J. (2019). La investigación social sobre las violencias hacia las personas LGBTQ+. In Varios Autores (Ed.), Mucho género que cortar: Estudios para contribuir al debate sobre género y diversidad sexual en Chile. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362658696_GEDIS-MUCHO_GENERO_QUE_CORTAR_Santiago_2022

Boden-Stuart, Z., McGlynn, N., Smith, M. C., Jones, H., & Hirani, R. (2022). Pathways between LGBTQ migration, social isolation and distress: liberation, care and loneliness. Retrieved from https://research.brighton.ac.uk/files/33527541/Pathways_between_LGBTQ_migration

Galaz Valderrama, C., Cea, P., Molina, D., Castro, D., & Ortega, M. J. (2022). Una mirada interseccional a las prácticas de salud en Aysén. Procesos de racialización en Chile. Quaderns de Psicologia, 23(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.1750

Goetz, T. G., & Keuroghlian, A. S. (2024). Gender-affirming Psychiatric Care (T. G. Goetz & A. S. Keuroghlian, eds.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing.

Martínez, C., Tomicic, A., & del Pino, S. (2019). Disparidades y Barreras de Acceso a la Salud Mental en Personas LGBTI+: El Derecho a una Atención Culturalmente Competente [Disparities and Barriers to Access to Mental Health in the Case of LGBTI+ People: The Right to Culturally Competent Care]. In F. Vargas Rivas (Ed.), Informe Anual sobre Derechos Humanos en Chile 2019 (pp. 397–446). Ediciones Universidad Diego Portales.

Reyes Espejo, M. I., Mayorga, C., & Araújo Menezes, J. de. (2017). Editorial: Psicología y Feminismo – Cuestiones epistemológicas y metodológicas. Psicoperspectivas. Individuo y Sociedad, 16(2). https://doi.org/10.5027/psicoperspectivas-Vol16-Issue2-fulltext-1116

Zeeman, L., Sherriff, N., Browne, K., McGlynn, N., Mirandola, M., Gios, L., … De Sutter, P. (2019). A review of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex (LGBTI) health and healthcare inequalities. European Journal of Public Health, 29(5), 974–980. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky226